I love food, all kinds of food. Gourmet food, soul food, street food, ethnic food, home cooking. So I thought it would be amusing to do a little research on Greek cuisine, because it’s fun to think we have a lot of the same things on our plate as Plato (forgive the pun!)

Some Greek recipes have existed for thousands of years, especially those including local produce such as oranges and lemons, pomegranates, tomatoes, grapes, figs. And, of course, olive oil – our liquid gold.

The first cookbook ever to be written is credited to Archestratus, a Greek poet living in Sicily around 350 B. C. It’s a poem called Υδηπάθεια (Life of Luxury) written in hexameters, of which only 62 fragments survive. The poem is in fact a gastronomic guide, where the author tells of his travels around the Mediterranean in search of the best food and wine. Like today’s foodies, Archestratus loved learning the culinary traditions and customs of different places. He believed in the importance of quality ingredients, which had to be fresh and in season, and cooked simply, with little fat, using seasoning lightly in order to enhance and not mask their flavor.

He focused mainly on fish, being a big fan of tuna, but also of mullet, sea bass, swordfish and squid. One of his recipes is for tuna wrapped in fig leaves, cooked under the ashes and flavored with olive oil and oregano.

But even before Archestratus, the Greeks were interested in good food. Aristaios (or Aristaeus) was the god of shepherds and cheese-making, bee-keeping, honey, honey-mead, olive growing and medicinal herbs. His name was derived from the Greek word aristos, “most excellent” or “most useful.” It seems he started life a mortal, but was made a god because of his services to mankind.

The Greeks invented bread; they made wine which they flavored with thyme, mint, cinnamon or honey and stored in clay pots, amphoras, which they marked with the year and origin. They drank their wine cut with water, to keep their wits about them, and thought drinking undiluted wine a barbarian custom.

They cultivated orchards of fruit and nut trees, and raised swine, goats, sheep and cows, as well as chickens, ducks, geese and swans. They grew an abundance of vegetables and gathered myriad greens. Fish was essential to their diet but they ate little meat. They enhanced dishes with wild oregano and sage and imported cinnamon and pepper.

The Greek diet has been influenced by both the East and the West. In ancient times, the Persians introduced Middle Eastern foods, such as yogurt, rice, and sweets made from nuts, honey, and sesame seeds. When Rome invaded Greece, the Romans brought with them foods that are typical in Italy, such as pasta and sauces, and the thin phyllo pastry dough used to make sweet and savory pies. Then came the Ottoman conquerors, with assorted Central Asian dishes like rice pilaf and loukoum – Turkish Delight, flavoured with rose water. Arab influences added spices such as cumin, cinnamon, allspice, and cloves, and introduced coffee to Greece. Potatoes, pumpkins and tomatoes were later brought from the New World.

For Greeks, food and eating did not just satisfy physical needs; it was primarily a social event. Plutarch, a Greek historian, said, “We do not sit at the table to eat… but to eat together”. This idea of conviviality has resulted in the meze tradition of sharing a multitude of small dishes, which has spread throughout the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

In Greece today you will still find all the foods that have been eaten through the ages: plates of fava, a puree of yellow split peas topped with wild capers, onions, or marinated sardines; tomatoes, peppers, cabbage and vine leaves stuffed with meat or rice, pine nuts, sultanas, cheese; λαδερά (ladera), vegetables braised in olive oil; meats simply grilled or cooked with tomatoes and wine; fish and seafood of all kinds; meats and greens encased in delicate phyllo pastry. Food is seasoned with sea salt, onion, garlic, oregano, thyme, rosemary and mint, as well as cumin, cinnamon, allspice and chili pepper.

For dessert, the same phyllo pastry enfolds fruit and nuts and is bathed in honey syrup and sprinkled with cinnamon. A simple dish of yogurt is topped with walnuts and drizzled in honey. And there’s always fruit: apples, pears and citrus fruits in winter, cherries, apricots, strawberries in the spring, peaches, watermelons, melons and figs in summer, grapes, quinces and pomegranates in fall. Of course now you can get fruit out of season, as well as exotic fruits like bananas, pineapples and mangoes. But Greeks generally like to buy things in season.

Greek chefs today have taken this rich tradition and given it a modern twist. You will find them plying their trade in Athens, but also in other cities, on the islands and on the mountains. The success of the tourist trade, as well as the popularity of tv cooking shows has made the profession lucrative for many young people. They like to use local produce in season, bring a fresh take to old recipes, and also use ideas and influences from other countries.

Greece produces a wide variety of cheeses, from the ubiquitous feta and other soft, fresh cheeses, to hard cheeses such as γραβιέρα (graviera) and κεφαλοτύρι (kefalotyri). Every region also produces their own local cheeses – always ask to sample them when traveling.

The first Greek wine has been dated about 6,500 years ago, and, in recent years, the Greek wine industry has been undergoing a renaissance. Improvements have been made with serious investments in modern wine making technology. The new generation of native winemakers is being trained in the best wine schools around the world and their efforts are paying off as Greek wines continue to receive the highest awards in international competitions. What makes Greek wine so unique are the more than 300 indigenous grape varieties grown here, some of which have been cultivated since ancient times. Many well-known international grape varieties are also used in Greek wine making.

Greeks love to eat outdoors, and will do so all year round, weather permitting.

Following the tradition of hospitality, people will welcome you into their homes with a glass of water and a spoonful of γλυκό (glyko) – preserves made with fruit such as sour cherries or citrus peel, flowers such as rose petals and lemon tree buds, and also fruit and vegetables not yet ripe, such as tiny aubergines, green walnuts, tiny green mandarins and figs.

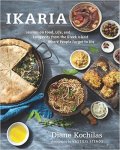

For those interested in trying their hand at some Greek specialities, there are many good cookbooks in English. For example, the lovely series written by Diane Kochilas;

For those interested in trying their hand at some Greek specialities, there are many good cookbooks in English. For example, the lovely series written by Diane Kochilas;

or Vefa’s Kitchen, the bible of Greek cuisine by the grande dame of Greek cooking.

or Vefa’s Kitchen, the bible of Greek cuisine by the grande dame of Greek cooking.

There are also a few great blogs, such as Little Cooking Tips, which features delicious recipes. They kindly allowed me to borrow their lovely photographs of food, all of which could have been in Plato’s plate.

And, by the way, Bon appetit in Greek is Καλή Όρεξη (Kali Orexi)!

The pomegranate smashes to the floor and the red grains scatter in all directions, spreading good fortune in the household, office or shop.

The pomegranate smashes to the floor and the red grains scatter in all directions, spreading good fortune in the household, office or shop.

Fresh carrots are also amazing this time of year, and a very versatile ingredient. We used them in soups (especially fasolada bean soup), in coleslaw, made carrot cakes, and so on and so forth:)

Fresh carrots are also amazing this time of year, and a very versatile ingredient. We used them in soups (especially fasolada bean soup), in coleslaw, made carrot cakes, and so on and so forth:) Do you remember the green oranges back in the summer? Check them out in the photo of this post! Ripe and sweet, this year’s oranges are perhaps the best in years. And for some strange reason the trees in Evia were very generous, we got much more than we can eat, turn into jams, preserves etc. So we started sharing them with friend, like an Orange Santa, passing by on a weekly basis.

Do you remember the green oranges back in the summer? Check them out in the photo of this post! Ripe and sweet, this year’s oranges are perhaps the best in years. And for some strange reason the trees in Evia were very generous, we got much more than we can eat, turn into jams, preserves etc. So we started sharing them with friend, like an Orange Santa, passing by on a weekly basis. A big part of the Greek Christmas tradition is of course the sweet treats:melomakarona, kourabiedes and diples. Melomakarona and kourabiedes are the most popular ones, and if you’re in Greece around Christmas you’re bound to fall in love with them. You will find them in every household, any pastry shop, even in super markets and grocery stores. When you’re a guest, you know you’ll be treated a melomakarono (singular for melomakarona) or a kourabies (singular for kourabiedes). And even though you most certainly will have tasted many of them already, you will devour this treat with pleasure.

A big part of the Greek Christmas tradition is of course the sweet treats:melomakarona, kourabiedes and diples. Melomakarona and kourabiedes are the most popular ones, and if you’re in Greece around Christmas you’re bound to fall in love with them. You will find them in every household, any pastry shop, even in super markets and grocery stores. When you’re a guest, you know you’ll be treated a melomakarono (singular for melomakarona) or a kourabies (singular for kourabiedes). And even though you most certainly will have tasted many of them already, you will devour this treat with pleasure. Those traditional, shortbread butter cookies include almonds, lots of powdered sugar, vanilla and usually rosewater or other flower water.

Those traditional, shortbread butter cookies include almonds, lots of powdered sugar, vanilla and usually rosewater or other flower water. Regarding the shape of those cookies, some people may be confused due to the variety. There are 3 main shapes for kourabiedes: thick round cookies, crescents and balls. We think the easiest and nicest are the thick round cookies, as the shape helps in stacking up the cookies in layers, as they’re traditionally served.

Regarding the shape of those cookies, some people may be confused due to the variety. There are 3 main shapes for kourabiedes: thick round cookies, crescents and balls. We think the easiest and nicest are the thick round cookies, as the shape helps in stacking up the cookies in layers, as they’re traditionally served. If using raw almonds, place them in a single layer on a lined baking sheet/pan and bake them for 10-15 minutes at 180C/350F (preheated oven) (pic. 1). Grind the toasted almonds in small pieces, using a food processor. Do not grind them into powder.

If using raw almonds, place them in a single layer on a lined baking sheet/pan and bake them for 10-15 minutes at 180C/350F (preheated oven) (pic. 1). Grind the toasted almonds in small pieces, using a food processor. Do not grind them into powder. Making the cookies:

Making the cookies: Add the powdered sugar (pic.4) and beat for 10 more minutes until you get a “whipped cream” -like result (pic. 5).

Add the powdered sugar (pic.4) and beat for 10 more minutes until you get a “whipped cream” -like result (pic. 5). Add baking powder, vanilla (pic. 6) and mix with a rubber spatula. Add the egg yolk (pic. 7) and mix until it’s incorporated.

Add baking powder, vanilla (pic. 6) and mix with a rubber spatula. Add the egg yolk (pic. 7) and mix until it’s incorporated. Add 1 tablespoon of rosewater or flower water and mix (pic. 8). Start adding the flour (pic. 9), a couple of tablespoons at a time. Mix with the spatula each time you add some.

Add 1 tablespoon of rosewater or flower water and mix (pic. 8). Start adding the flour (pic. 9), a couple of tablespoons at a time. Mix with the spatula each time you add some. When you’ve added half the flour, you’ll get a fluffy, almost rubbery dough (pic. 10).

When you’ve added half the flour, you’ll get a fluffy, almost rubbery dough (pic. 10). Add the ground almonds (pic. 12) and fold them into the dough. Shape the cookies (pic. 13). If using 40gr/1.5oz of dough per cookie, you’ll make about 25 cookies.

Add the ground almonds (pic. 12) and fold them into the dough. Shape the cookies (pic. 13). If using 40gr/1.5oz of dough per cookie, you’ll make about 25 cookies. Place the cookies in a lined baking dish/pan (pic. 14) and bake for 15-18 minutes in the middle rack (use the oven fan in preheated oven). Remove from the oven,let them cool for 2-3 minutes, and then place them on a rack to dry out (pic. 15). Let them to cool completely.

Place the cookies in a lined baking dish/pan (pic. 14) and bake for 15-18 minutes in the middle rack (use the oven fan in preheated oven). Remove from the oven,let them cool for 2-3 minutes, and then place them on a rack to dry out (pic. 15). Let them to cool completely. Spray them with rosewater or flower water (pic. 16) and dust them with powdered sugar (pic. 17). Be generous with both.

Spray them with rosewater or flower water (pic. 16) and dust them with powdered sugar (pic. 17). Be generous with both.