Here’s wishing you all a happy, healthy and prosperous new year. And hoping for Peace on Earth, although it doesn’t seem very likely at the moment…But one must remain positive.

Here’s wishing you all a happy, healthy and prosperous new year. And hoping for Peace on Earth, although it doesn’t seem very likely at the moment…But one must remain positive.

I seem to be in a poetic mood lately, so here’s a seasonal one by Robert Frost.

A Christmas circular letter by Robert Frost.

The city had withdrawn into itself

And left at last the country to the country;

When between whirls of snow not come to lie

And whirls of foliage not yet laid, there drove

A stranger to our yard, who looked the city,

Yet did in country fashion in that there

He sat and waited till he drew us out,

A-buttoning coats, to ask him who he was.

He proved to be the city come again

To look for something it had left behind

And could not do without and keep its Christmas.

He asked if I would sell my Christmas trees;

My woods—the young fir balsams like a place

Where houses all are churches and have spires.

I hadn't thought of them as Christmas trees.

I doubt if I was tempted for a moment

To sell them off their feet to go in cars

And leave the slope behind the house all bare,

Where the sun shines now no warmer than the moon.

I'd hate to have them know it if I was.

Yet more I'd hate to hold my trees, except

As others hold theirs or refuse for them,

Beyond the time of profitable growth—

The trial by market everything must come to.

I dallied so much with the thought of selling.

Then whether from mistaken courtesy

And fear of seeming short of speech, or whether

From hope of hearing good of what was mine,

I said, "There aren't enough to be worth while."

"I could soon tell how many they would cut,

You let me look them over."

"You could look.

But don't expect I'm going to let you have them."

Pasture they spring in, some in clumps too close

That lop each other of boughs, but not a few

Quite solitary and having equal boughs

All round and round. The latter he nodded "Yes" to,

Or paused to say beneath some lovelier one,

With a buyer's moderation, "That would do."

I thought so too, but wasn't there to say so.

We climbed the pasture on the south, crossed over,

And came down on the north.

He said, "A thousand."

"A thousand Christmas trees!—at what apiece?"

He felt some need of softening that to me:

"A thousand trees would come to thirty dollars."

Then I was certain I had never meant

To let him have them. Never show surprise!

But thirty dollars seemed so small beside

The extent of pasture I should strip, three cents

(For that was all they figured out apiece)—

Three cents so small beside the dollar friends

I should be writing to within the hour

Would pay in cities for good trees like those,

Regular vestry-trees whole Sunday Schools

Could hang enough on to pick off enough.

A thousand Christmas trees I didn't know I had!

Worth three cents more to give away than sell,

As may be shown by a simple calculation.

Too bad I couldn't lay one in a letter.

I can't help wishing I could send you one,

In wishing you herewith a Merry Christmas.

🎄And a very Merry Christmas from me too, to you all.

As the year draws to a close, I though I’d make a short list of the best books I read this year—the books I personally liked best, because obviously opinions differ. I was inspired by Jacqui Wine’s Journal—I’ve followed her for years, because our tastes coincide, and I’ve had many wonderful recommendations from her over time. If you haven’t come across her Blog, I urge you to take a look, especially if you are a fan of solid storytelling and excellent writing. She also often revisits old favourites, as well as books in translation.

Since I do like variety in my reading, my list is quite eclectic. Here are the ten I savoured most, not in any particular order.

Wild Thing, by Suzanne Prideau, a truly exceptional life of Paul Gaugin, which I reviewed a little while ago Here

Days at the Morisaki Bookshop and More Days At the Morisaki Bookshop, to coincide with my trip to Japan. Life in Tokyo through the eyes of a young woman. Amusing and different (and a cool cover!). Buy it: Here

Human Matter, by Rodrigo Rey Rosa, a well-known Guatemalan writer. A semi-autobiographical dive into the realities of a dictatorial regime, seen through its bureaucracy. Engrossing if harrowing. Here

The Forbidden Notebook, by Alba de Cespedes. One of Jacquie’s suggestions, about the daily life of an Italian housewife in the 50s. Fascinating. Here

Stone Yard Devotional, by Charlotte Moore. One of the Booker Prize shortlist for 2024. Very original and atmospheric. I got caught up in a very absorbing story. Here

The Game of Hearts, by Felicity Day. Part of my research into the Regency era. The stories of real women of that time—often, truth is stranger than fiction. Or more amusing. Here

Longbourn, by Jo Baker. Pride and Prejudice from behind the mirror: the daily life of the Bennet household as seen through the eyes of their servants. Here

Horse, a novel, by Geraldine Brooks. A great story told over two time lines, based on the real champion thoroughbred Lexington. With added enjoyment for people who love horses. Here

The Safekeep, by Yale Van Der Wooten. Another book shortlisted for the Booker Prize, this is an original story of the developing relationship between two very different women staying in the same house in the Dutch countryside during the summer of 1961. It is well plotted and in turns mysterious and unnerving. Here

The Golden Child. I love Penelope Fitzgerald and this was one that, most surprisingly, I had not read. Like an immersion in a warm bubble bath. Did not disappoint. Here

Add to those a couple of thrillers, some Regencies (good and not so good), and a handful of crime novels (I especially enjoy those of Vaseem Khan, set in India with a most interesting policewoman heroine.) I’ve also been reading books by people whose blogs I’ve been following for years and who have been most supportive of my own book. They’ve been on my TBR list for a while, but—so many books, so little time, as I keep repeating.

Well, I do hope some of the above will appeal to you. Happy reading! (Or perhaps you’ve e read them all?)

Talk about leaving something behind! Tom Stoppard, who has just died, aged 88, wrote—over the course of five decades—35 stage plays (including seven translations or adaptations of foreign work), 11 radio plays, 6 television plays, and 14 film and television adaptations of books and plays. An opus which will keep his memory fresh for years to come.

I am not about to write an obituary complete with all his life details. Every newspaper has done that, and writer, journalist and magazine editor Tina Brown, who knew him personally since she was a teenager (he lived close to them and was friends with her father) has posted a lovely eulogy on Substack.

Stoppard wrote great theatre because he wrote great dialogue, witty and argumentative. In his own words, ‘Writing plays is the only respectable way of contradicting oneself.’

Here is a description of him, from an obituary in the Guardian:

A tall and strikingly handsome man, with a long, bloodhound face, a thick tangle of hair and a casually assembled wardrobe of expensive suits, coats and very long scarves, Stoppard cut an exotic, dandyish figure, a valiant and incorrigible smoker who moved easily in the highest social and academic circles, a golden boy eliding into middle-aged distinction and never losing the thick, deliberate accent of his origins, even though he never spoke Czech. He carved out his career in his own always carefully chosen words. He was often thought to be “too clever by half,” but never patronised audiences by talking down to them, even if they had to work hard to keep up.

Stoppard lived a charmed life in England, something he was always grateful for, considering a large part of his family died in the camps. This part of his personal history he only got to research in later years.

In my case, I credit Stoppard for instilling in me an eternal love of the theatre. Not living in England, I sadly did not manage to see all his plays, but I made it a point to see as many as I could, and they remain vivid in my memory. The wit, the irony, the sarcasm, the erudition and, above all, the sheer enjoyment.

Rozencrantz And Guidenstern Are Dead, The Real Inspector Hound, Arcadia, India Ink…The list goes on. Wonderful actors, such as Bill Nighy and the incomparable Felicity Kendall, fantastic sets. A great director, for a lot of them, in the shape of Peter Wood.

He’s always been number one in my list of people to invite to an imaginary dinner party. May you rest in peace, Mr Stoppard, and thank you.

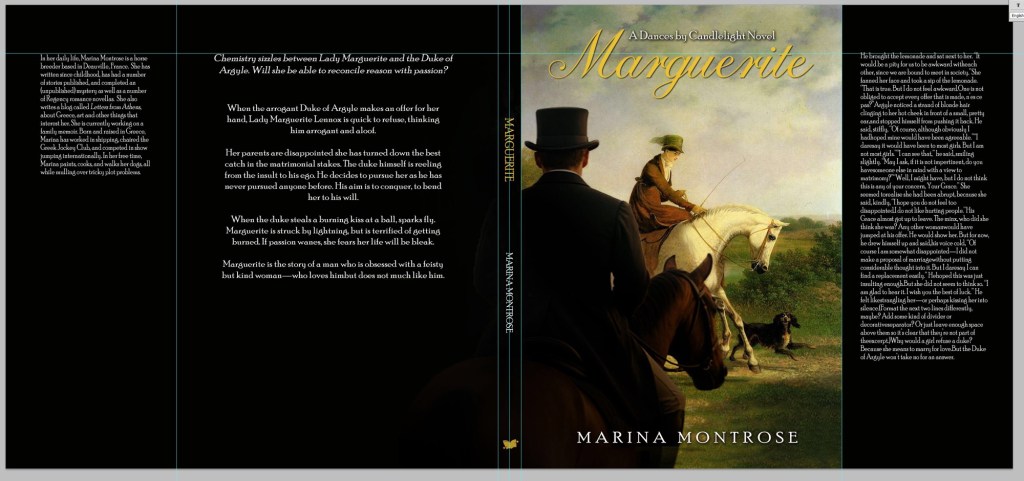

Things are moving fast all at once. After months of idleness, publication date for my debut novel, Marguerite, has been set for December 4. Very exciting!

While waiting for the publishers to reveal their complete marketing plan, I have been am busy setting up my side of things. I think I mentioned before that I joined the Author’s Guild of America, which was a shrewd move. They provide free tools to build a website (they can also build it for you if you like). They organised my domain name and an email in my pen name. They embedded the email sign-up form into the website. And the best—you communicate with a REAL PERSON (shoutout to Hector!) No bots, and no endless search for some elusive ‘Happiness Engineer’. Yay.

As for the rest, why must everything be so complicated? I was assured by Kindlepreneur (a very useful source of all kinds of information) that the best mailing service for authors is MailerLite, as well as being the easiest to set up. Well, either I’m a moron, or the other services need a degree in advanced coding. I have been struggling with the damn thing for days—despite a bot who is better than most, and even some help from a real live person. But it’s done, more or less. Finally, I’m pretty familiar with IG, via my art account, but I hate X, Facebook etc. I think I’ll pass. I’m too old to make little videos on TikTok.

Take a look at the cover and tell me what you think. I’m quite pleased with it. I was very clear about NO bare-chested duke clutching a swooning maiden.

It was difficult for the graphic artist to find a stock photo I liked, so I came upon the idea to use an old painting (in the public domain). This is an oil portrait by Swiss artist Jacques-Laurent Agasse (1767 – 1849), possibly of Mademoiselle Cazenove. Then I wanted to superimpose a profile of the duke watching Marguerite ride in the park. The graphic artist did a good job of my ideas, I think.

Finally, a bout of shameless self-promotion:

I am delighted to present my debut novel, Marguerite. Set in the elitist and socially restricted milieu of the ton in Regency London, it is the story of an independent, opinionated girl and the man who pursues her despite her refusing his offer of marriage.

If this sounds like your cup of tea, I would be grateful if you would consider preordering the book. Preorders help new authors get discovered, and your support is invaluable.

Once you’ve read the book (if you manage to finish and if you haven’t hated it!), I would love it if you would consider leaving a review. Even a sentence helps other readers find the book, and I am interested in every piece of feedback.

I’d also like to invite you to take a look at my website, Marina Montrose Author, where subscribers to the Reader’s Club receive a free, exclusive short story as a thank you gift. You can join here:

https://www.mmontrose.com/disc.htm

Thank you for being part of this adventure. 📚

P.S. The book is available for preorder on Amazon, but print copies only on Amazon.com still…Here is a link to all the other places where you can preorder. Or order later on.

https://cupidsarrowpublishing.com/marguerite

A few days ago I went to Paris to visit a friend, who lives right next to the Musée d’Orsay, in a bustling neighbourhood on the Left Bank. After a delicious lunch that she had prepared for me, we wandered over to the museum, which has always been a great favourite.

A conversion of the Gare d’Orsay, a Beaux-Arts railway station built in the late 19th century, the building itself is amazingly beautiful, with stunning views of Paris out of every window. Regular readers will know I visit as often as I can, and have written about exhibitions by Picasso, Caillebotte and others (for those interested, putting “Musée d’Orsay” in the finder will lead you to them).

The permanent collection is full of treasures, and every time I go I discover something new amongst the old favourites. My friend and I walked around, admiring the Gaugin paintings some of which I had read about in Sue Prideaux’s biography,Wild Thing (reviewed in a recent post).

Another lovely painting, the portrait, by Odilon Redon, of Baronne Robert de Domecy

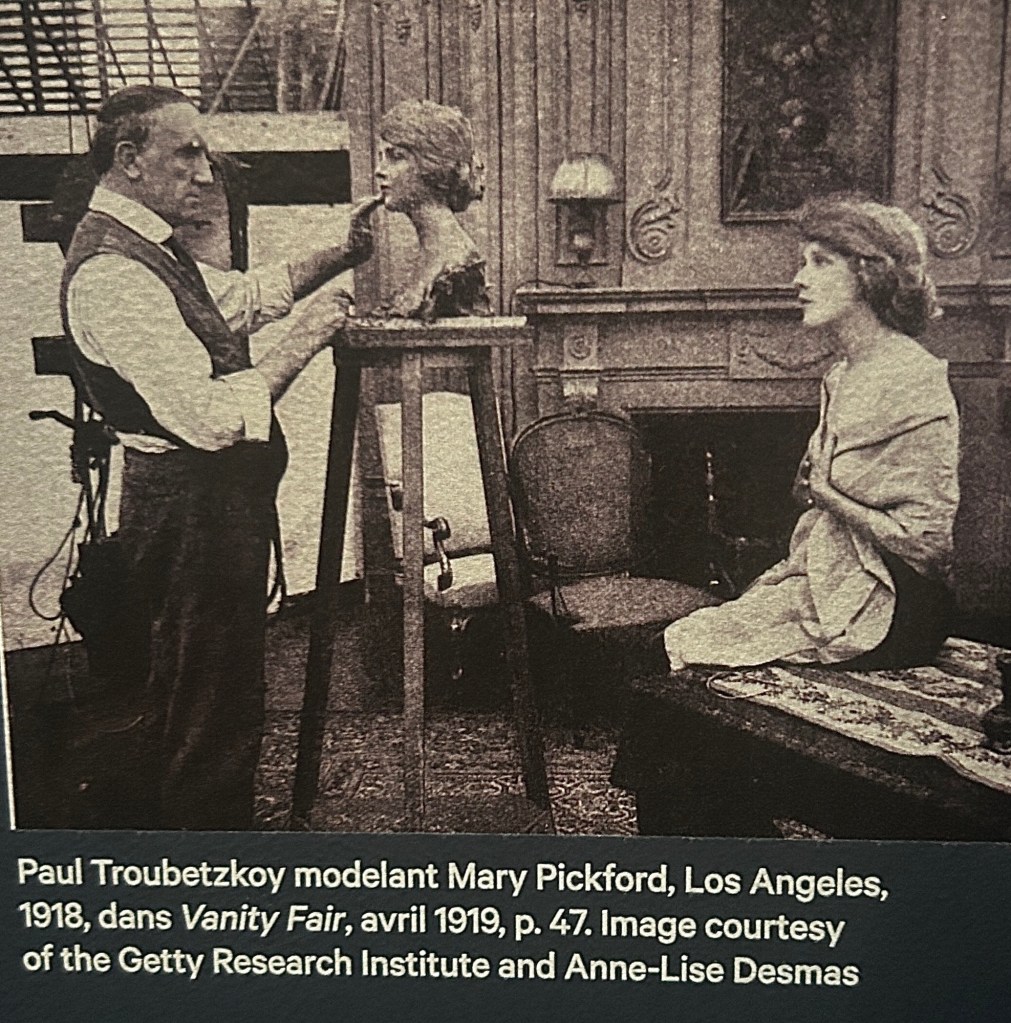

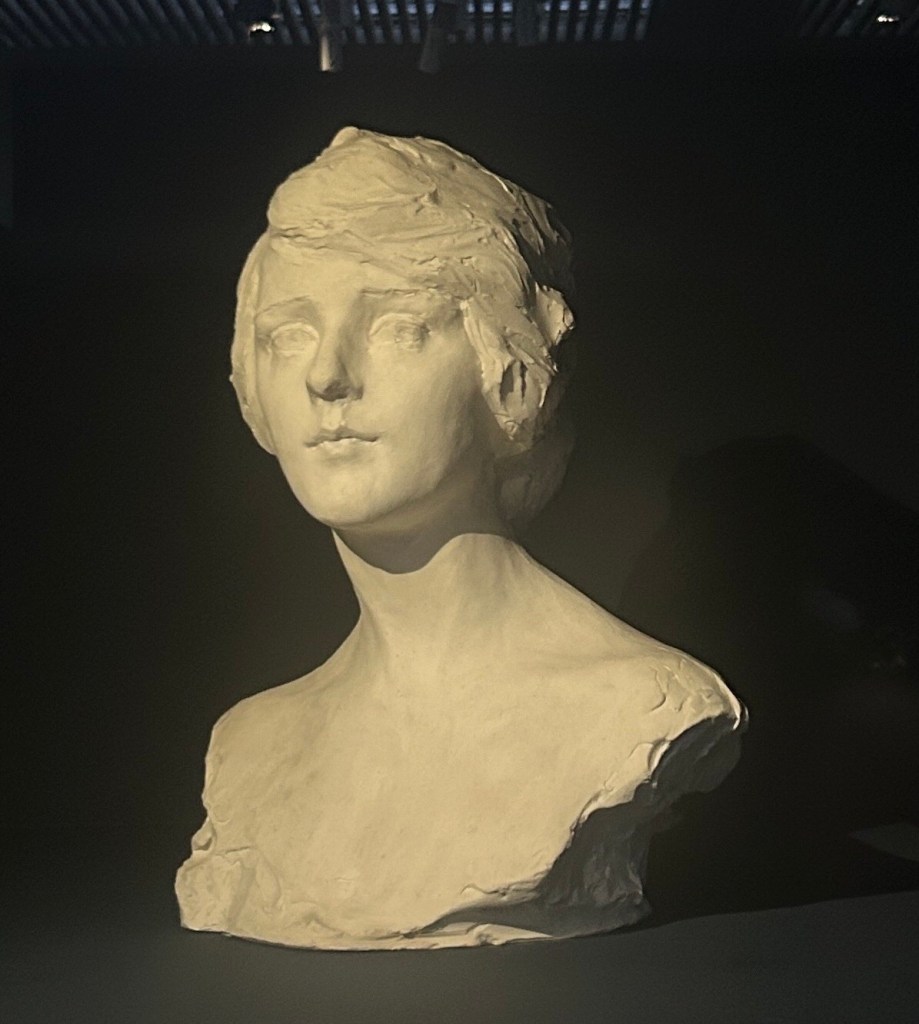

This time the temporary exhibition was of the previously unknown to me sculptor Paul Troubetzkoy (1866-1938).

Troubetzkoy, who was an iconic figure of his time, was the illegitimate child of a Russian diplomat and an American singer and pianist. He was acknowledged by his father at the age of five, trained in Milan and started his career in Moscow and St Petersburg, where he was well received by the local elite, despite speaking virtually no Russian. Having a wonderful facility of capturing people’s likeness in clay (which he then cast in bronze) he sculpted numerous portraits of the aristocracy, but his masterpiece of that period was the portrait of Tolstoy, a vegetarian who made a profound impression upon him (and converted him to the cause).

In 1906, when Russia was racked by the first throes of revolutionary unrest, Troubetzkoy left for Paris, where he quickly won over Parisian society. Bohemian and eccentric, he walked his domesticated wolves in the Bois de Boulogne, and hobnobbed with the city’s cosmopolitan elite, earning numerous portrait commissions. He perfected the genre of portrait statuettes that would make him famous—Anatole France, George Bernard Shaw, Auguste Rodin, Baroness de Rothschild and Roland Garros were amongst those who posed for him.

He also loved to depict children and animals. His passion for the latter was the reason he became a vegetarian.

He suffered unbearable tragedy when his only son, Pierre died at the age of two and a half—just after he had sculpted a moving portrait of him with his mother, Paul’s wife Elin.

Troubetzkoy also had much success in America, where he travelled three times between 1911 and 1912, then stayed for almost seven years (1914-1920), again attracting numerous commissions.

Here he is sculpting the actress Mary Pickford. Amazing how he works in a waistcoat, shirt and tie! He also had a magnificent comb-over…

And the finished portrait.

I adored this lovely statuette of an Arabian horse.

Troubetzkoy returned to Europe in 1920, where he settled in France and stayed until his death in 1938 at the age of 72, travelling often to Italy and continuing to sculpt portraits of political figures and representatives of cosmopolitan high society in both countries.

Josepha, the young woman who runs the art studio I attend on Mondays and (when possible) Tuesdays, has set up a Saturday afternoon painting session she calls apéro peinture. The idea is to attract outsiders who are beginners and just want to try painting, but this has had mixed results. Attendance varies. So, a group of the usual suspects decided to take over yesterday, to while away a rainy afternoon.

The idea is not to take ourselves seriously, but interpret the subject as the fancy takes us. We all sit around a table set with small easels, boards and acrylic paints and we all paint from the same model, provided by Josepha. We are fuelled by apple cider, wine and tidbits.

Yesterday the inspiration was a work by Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938), a French painter who in 1894 became the first woman painter admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. She was also the mother of painter Maurice Utrillo. The painting is of a, shall we say, corpulent woman lying on a couch, smoking.

What is always interesting in such situations, is how differently people interpret the same subject. In barely two hours we were supposed to finish a small painting (acrylics dry fast), and this was accomplished amid a lot of banter. We always mock each other mercilessly and have to defend our choices.

Christophe and I decided to omit the cigarette, on the pretext that smoking is unhealthy and Non-PC; Philippe on the contrary gave the woman a spliff and drew her levitating above the couch, with three balloons hovering above; and Nathalie actually put her in a bathtub!

Josepha was accompanied by her baby, Garance, her mother (to look after Garance who has just learned to walk), her dog Odin (who is a frequent visitor to the studio) and her partner Tommy who is a journalist and does not draw of paint. His first effort was quite creditable.

Needless to say, a merry afternoon was had by all. However, the artistic benefits are not to be understated, as this type of exercise allows one to let go of rules like perspective and colour values and give free rein to one’s imagination.

My finished version. Cigarette apart, I did not stray too far from the original.

Now that summer stone fruit are over, it is time for the humble pear to take up the slack. OK, an apple a day keeps the doctor away, and here in Normandy we are spoilt for choice with crisp, sweet-tasting apples.

The pear, however, must not be disregarded, although it is a bit of a bother to get it right—one minute they are stone hard, the next nearly too soft. One must always keep an eagle eye on them.

Pears are lovely eaten with some kind of blue cheese—Saint Agur, Fourme D’Ambert or Stilton—and walnuts. And the lot is good in a fresh green salad. Here in Normandy they make a refreshing pear cider, called poiré; but pears are great cooked, too. Poached in red wine or maple syrup, or baked with honey, vanilla and ginger.

I have discovered a wonderfully easy and deliciously homey recipe for pear cake, which I will herewith share with you.

CINNAMON PEAR CAKE

1 1/2 cup flour (I use a half-wholemeal flour but normal will do)

3/4 (scant) cup sugar

1 tsp. baking powder

1/4 tsp. salt

1 tsp. cinnamon

1 tsp. vanilla

1 egg

3/4 cup canola oil (I use half my Greek Olive oil)

2 pears or more, peeled and cut into chunks

2/3 cup walnuts (or pecans), chopped. Optional (mostly I don’t use them)

Easy one-bowl mixing. First mix the flour, sugar, BP, salt and cinnamon—add the vanilla and egg—mix in the oil—fold in the pears. The chunks needn’t be too small, and bits of pear should be poking out of the batter, otherwise add more. The batter will be very thick. Put in a greased tin and smooth as much as you can . I usually sprinkle some cane sugar on the top to give it some crunch. Bake in a pre-heated oven at 180 C for 45-55’ depending on your oven.

You’re welcome ☺️

How about some poetry instead of the relentless march of horrific news we are subjected to daily?

I never watch the news live anymore. I only scroll through the titles, glance diagonally in case something catches my attention and read pieces that interest me—about new books and films, art exhibitions, or people who do unexpected and funky things. My children mock me about being a fringe reader, but I do enjoy it.

Looking through available films on iTunes and elsewhere, I notice a huge number are horror movies. This is amazing to me—aren’t people horrified enough by what is happening in real life but they need to scare themselves further? To each his taste, I suppose.

Meanwhile, there is nothing more soothing than poetry, so I leafed through favourite books to find something to improve your day. Browsing, I realised a great number of poems deal with grief, loss, fear and other lowly feelings—of course, expressed in beautiful language. Nothing like newspaper articles, but still. Even the Romantics are very concerned with death and loss of love. However, there are poems to lift the heart, so here is one of them, about the transformative power of words, by Dylan Thomas.

Notes On The Art Of Poetry

I could never have dreamt that there were such goings-on

in the world between the covers of books,

such sandstorms and ice blasts of words,,,

such staggering peace, such enormous laughter,

such and so many blinding bright lights,, ,

splashing all over the pages

in a million bits and pieces

all of which were words, words, words,

and each of which were alive forever

in its own delight and glory and oddity and light.

After years of getting rejections for my writing, I finally signed with a publisher

If rejection letters were paper, I could have covered my bedroom walls with them (or made a bonfire). Thankfully, nowadays they are digital, so they remain hidden in an Excel sheet (just so that I can remember not to submit to the same agent/publisher twice!)

But let me go back a little: I have always loved writing from an early age, and in high school served as editor of the school mag, entitled Sunny Days. This activity alleviated hours of boredom in class, where I could correct texts and draw the artwork while the teacher droned on…

Earlier even than that, at age 10 or 11, I was let loose upon my mother’s bookshelves. She was a great fan of Agatha Christie and Georgette Heyer, both of whom I devoured (as well as a great variety of other authors, some more highbrow than others.)

Over the years, I wrote a number of short stories, some of which were placed in competitions, while others were published in Anthologies and online magazines (I got plenty of rejections there, too.)

I was (and am) a rabid bookworm, reading over a wide range of genres—literary fiction, memoir, short stories, historical novels, travel books. For entertainment I read mystery and crime. No romance.

Later I set myself the task of writing a book and of course I decided upon mystery. I took some online courses and attended the Festival of Writing at York twice (the most fun time). I completed no less than two novels, one set mainly on a yacht in the Greek islands, the next in the world of international horse racing. I really found it interesting and fun to work out the plot, the red herrings and twists and cliff hangers.

I started the process of querying agents but, although I got great feedback from some and quite a few requests for the full manuscript, the final answer was no. It was never the right timing, or quite the right thing for their list at this particular moment. Most just ghosted me, a practice I find at best impolite when they have requested the whole ms, however busy they might be. Publishers did reply, but still it was no.

I considered self-publishing but, after a lot of research, realised it would be very costly—both in money and time spent—in order to be done properly. Even if you self-edit to death, even if you find beta-readers for free, even if you design your cover yourself, it’s not enough. You need professional edits, a great cover, proper promotion. I’m not good enough to do it, don’t have the time or patience and I am too proud to press the button on a shoddy job. So I persevered and am still persevering.

Meanwhile, lockdown happened and, having more time on my hands, I started re-reading Jane Austen, whom I had not touched since school. She has stood the test of time for a reason. Then I went on to read some of Georgette Heyer again, and really enjoyed the banter and great writing. One thing led to another and, having shelved the mysteries (for now) I have written a number of Regency romance novellas.

Amazingly, I sent one off to an indie publisher and got a favourable reply! I was astonished, as I had actually forgotten about it. However, my excitement was quickly dampened because, after I signed the contract, they then went radio silent for the whole summer. Apparently one of the team had a medical problem, so delays were understandable, but emails went unanswered which freaked me out a little. I reached out to one of their authors who explained this can happen with indie presses because they are short staffed, and that patience was needed. But still.

However, they returned with a vengeance and now things are moving fast. My editor Lisa was lovely and actually there was not much to change or correct. The discussion about the cover went well. Publication date is early December, all fingers crossed—and I am panicking a little because there are so many things to do. I had to set up a Facebook page (I hate Facebook), and IG and X accounts. I have joined the Author’s Guild of America (the publisher, Cupid’s Arrow Press, is American) which is great: there’s a fantastic forum where you can get feedback and advice from other writers, they have tools for building a website, which I have done, and they even offer legal advice if you need it. But there is still a lot to do, and I am new at this.

My book is called Marguerite, which is the name of the heroine, but more about that in another post. I am using the pseudonym Marina Montrose for the novellas.

Stay tuned for further developments. I know historical romance is not everyone’s cup of tea, but I hope some of you at least will read and enjoy it. I would be honoured.