A few days ago I went to Paris to visit a friend, who lives right next to the Musée d’Orsay, in a bustling neighbourhood on the Left Bank. After a delicious lunch that she had prepared for me, we wandered over to the museum, which has always been a great favourite.

A conversion of the Gare d’Orsay, a Beaux-Arts railway station built in the late 19th century, the building itself is amazingly beautiful, with stunning views of Paris out of every window. Regular readers will know I visit as often as I can, and have written about exhibitions by Picasso, Caillebotte and others (for those interested, putting “Musée d’Orsay” in the finder will lead you to them).

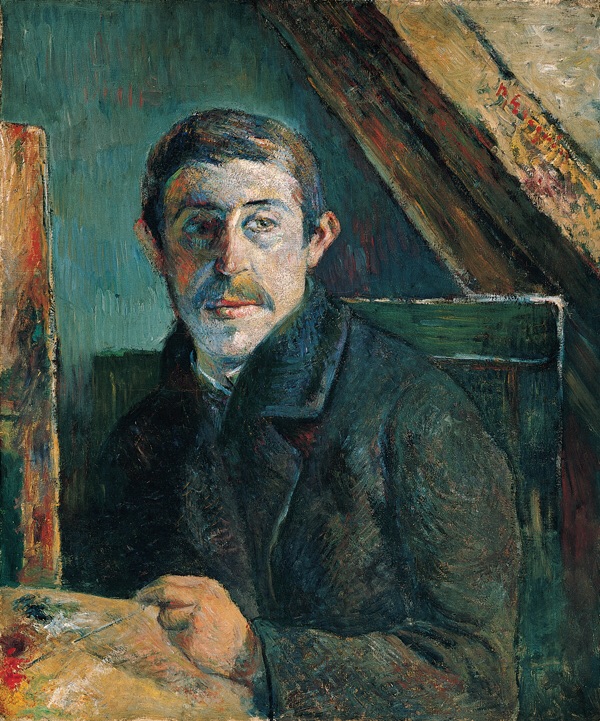

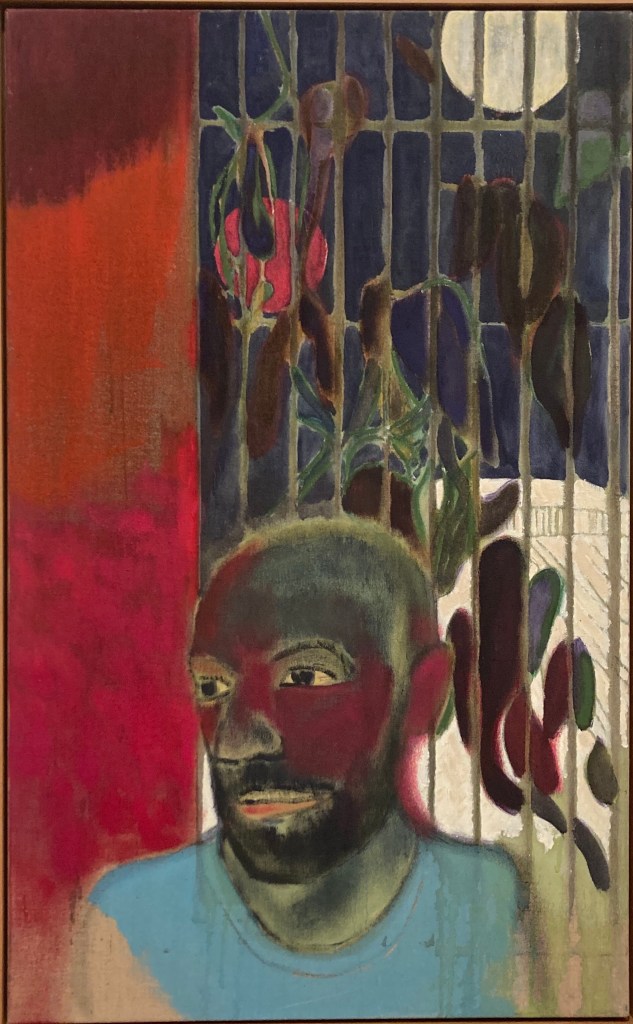

The permanent collection is full of treasures, and every time I go I discover something new amongst the old favourites. My friend and I walked around, admiring the Gaugin paintings some of which I had read about in Sue Prideaux’s biography,Wild Thing (reviewed in a recent post).

Another lovely painting, the portrait, by Odilon Redon, of Baronne Robert de Domecy

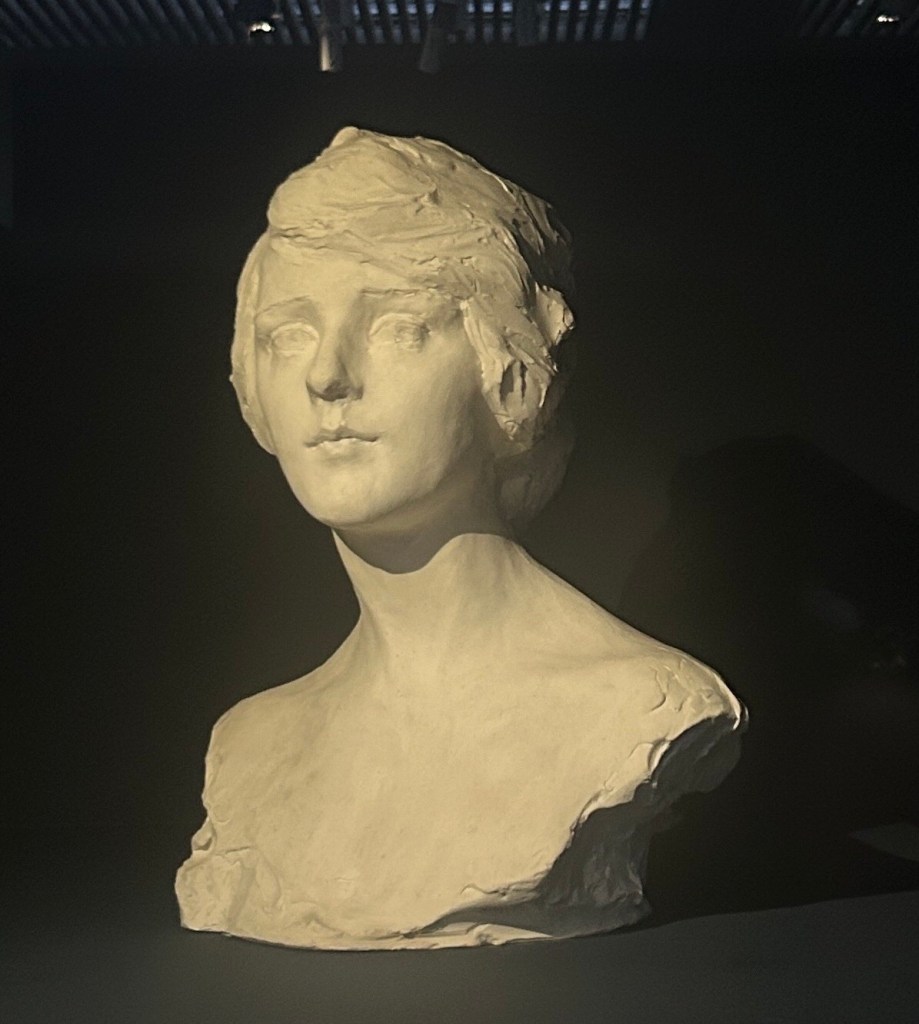

This time the temporary exhibition was of the previously unknown to me sculptor Paul Troubetzkoy (1866-1938).

Troubetzkoy, who was an iconic figure of his time, was the illegitimate child of a Russian diplomat and an American singer and pianist. He was acknowledged by his father at the age of five, trained in Milan and started his career in Moscow and St Petersburg, where he was well received by the local elite, despite speaking virtually no Russian. Having a wonderful facility of capturing people’s likeness in clay (which he then cast in bronze) he sculpted numerous portraits of the aristocracy, but his masterpiece of that period was the portrait of Tolstoy, a vegetarian who made a profound impression upon him (and converted him to the cause).

In 1906, when Russia was racked by the first throes of revolutionary unrest, Troubetzkoy left for Paris, where he quickly won over Parisian society. Bohemian and eccentric, he walked his domesticated wolves in the Bois de Boulogne, and hobnobbed with the city’s cosmopolitan elite, earning numerous portrait commissions. He perfected the genre of portrait statuettes that would make him famous—Anatole France, George Bernard Shaw, Auguste Rodin, Baroness de Rothschild and Roland Garros were amongst those who posed for him.

He also loved to depict children and animals. His passion for the latter was the reason he became a vegetarian.

He suffered unbearable tragedy when his only son, Pierre died at the age of two and a half—just after he had sculpted a moving portrait of him with his mother, Paul’s wife Elin.

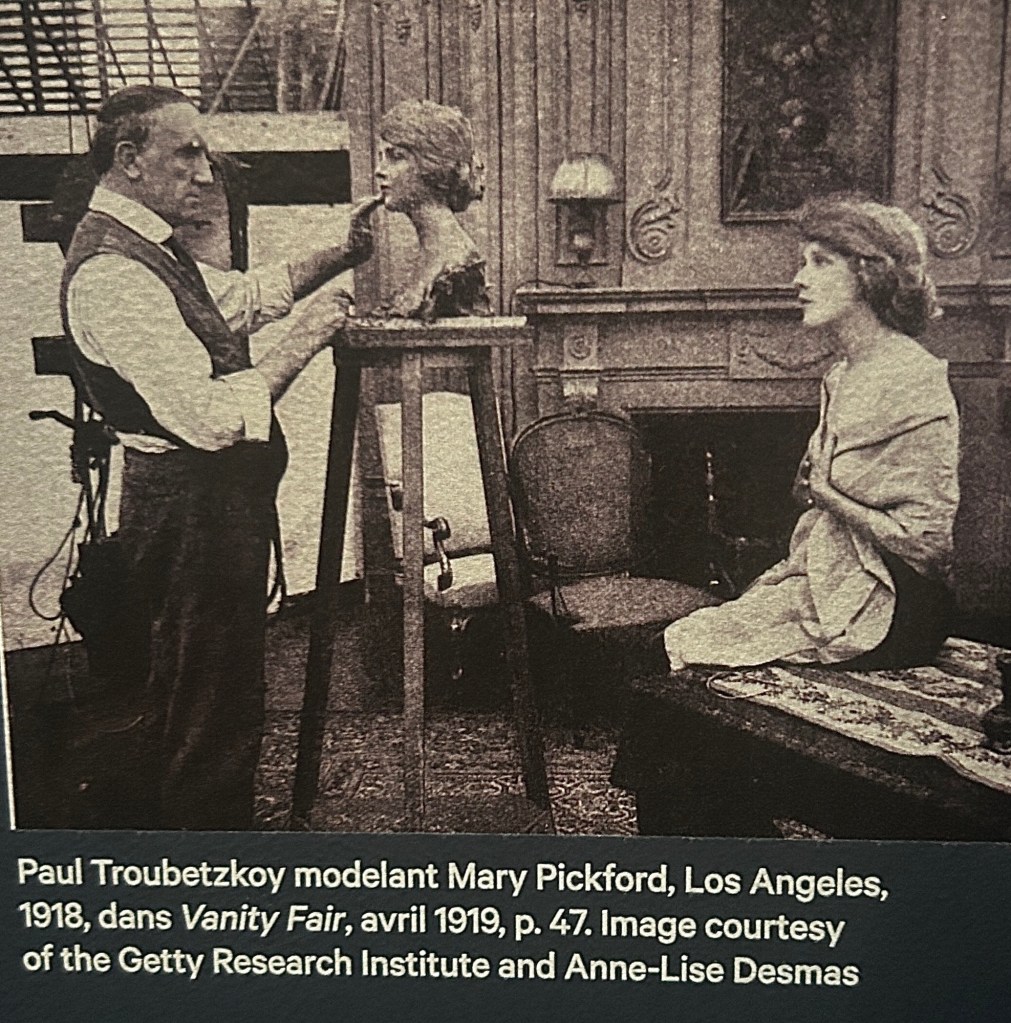

Troubetzkoy also had much success in America, where he travelled three times between 1911 and 1912, then stayed for almost seven years (1914-1920), again attracting numerous commissions.

Here he is sculpting the actress Mary Pickford. Amazing how he works in a waistcoat, shirt and tie! He also had a magnificent comb-over…

And the finished portrait.

I adored this lovely statuette of an Arabian horse.

Troubetzkoy returned to Europe in 1920, where he settled in France and stayed until his death in 1938 at the age of 72, travelling often to Italy and continuing to sculpt portraits of political figures and representatives of cosmopolitan high society in both countries.