Vivienne very kindly hosted me on her blog, Aspholessaria , and I am happy and honoured to return the favour. She writes mostly fantasy, which has not been my cup of tea so far, but I will now give it a try! I have already heavily promoted her to members of my family who are fans. And I have put her Viking books on my TBR list.

Here’s a bit about Vivienne:

V.M. Sang was born and lived her early life in Cheshire in the north west of England. She has always loved books and reading and learned to read before she went to school.

During her teenage years she wrote some poetry, one of which was published in Tecknowledge,the magazine of the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST). Unfortunately, that is the only one that is still around.

V.M. Sang became a teacher and taught English and Science at her first school.

She did little writing until starting to teach in Croydon, Greater London. Here she started a Dungeons and Dragons club in the school where she was teaching. She decided to write her own scenario. The idea of turning it into a novel formed but she did nothing about it until she took early retirement. Then she began to write The Wolves of Vimar Series.

Walking has always been one of V.M. Sang’s favourite pastimes, having gone on walking holidays in her teens. She met her husband walking with the University Hiking Club, and they still enjoy walking on the South Downs.

V.M.Sang also enjoys a variety of crafts, such as card making, tatting, crochet, knitting etc. She also draws and paints.

V.M.Sang is married with two children, a girl and a boy. Her daughter has three children and she loves to spend time with them.

She now lives in East Sussex with her husband.

⭐️

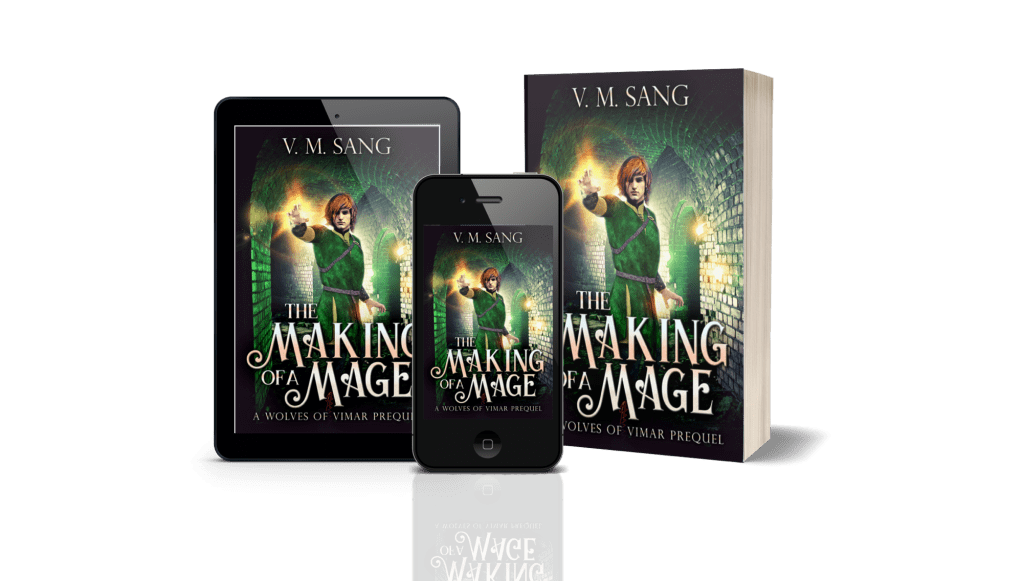

Unlike me with my one measly novella, Vivienne has been very prolific, and you will find links to her books below, and of course on her website. Here I would like to mention her novella, The Making of a Mage. It’s one of the Wolves of Vimar prequels and tells of the early life of Carthinal, one of the main characters in the series.

Blurb: Carthinal is alone in the world. His parents and grandparents have died. Without money and a place to live, he faces an uncertain future.

After joining a street gang, Carthinal begins a life of crime. Soon after, he sees a performing magician, and decides he wants to learn the art of magic.But can he break away from his past and find the path to his true destiny?

⭐️

And now onto our interview:

1. You have been very prolific. Do you spend many hours writing every day?

Not really. I’ve been rather bad recently and hardly written anything except a few poems. I think it’s because I’ve finished Book 4 of The Wolves of Vimar (Immortal’s Death) and am stuck on another couple of projects.

2. Do you finish one project before starting another, or do you have a few things on the go at once?

I usually have more than one thing on the go. I’ve started Book 3 of my Historical Novel series and I’m also writing a series of short stories inspired by fairy tales. The second story is going through a critique process at the moment and I’m partway through the third one. I’m also writing some poetry as I’ve been asked to submit some for an anthology.

3. Who is your favourite author/book?

Usually the last one I’ve read!

But seriously, I enjoy Fantasy and Science Fiction. I loved the Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan, but there are so many books and excellent writers.

One of my special favourites is Diana Wallace Peach. She writes fantasy in such a beautiful way.

4. If the above is not a classic, what is your favourite classic book?

I think Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte. She builds such a wonderful picture of the moors. Maybe I like it because of that. I used to live not far from that country and walked many times in my teens on those bleak moorland hills. Although they aren’t always bleak! In the heather season they are quite beautiful.

5. When we were children, Enid Blyton kept us up at night (with a torch under the covers) She is much criticised now, but she got many kids to read—as did JK Rowling, who is also criticised. I believe that is so important, above other considerations. Are your books read by children? Or teens and young adults?

I wholeheartedly agree with you about Enid Blyton. I loved her books when I was growing up, and they instilled a love of books in me.

I don’t consciously write for a particular age. My Elemental Worlds has been marketed as Young Adult. Someone said they thought Vengeance of a Slave was YA, but I disagree with that.

My books aren’t read by children. They are too long for a start, and I don’t think the language is children’s language. I don’t simplify words. Most YA books are also shorter than mine.

So no. They aren’t children or YA books.

6. If you have a proper job, what is it?

I used to be a teacher until I retired. Now I enjoy life! (If you get the chance to retire early, do so!)

7. Why do you write?

There are stories in my head trying to get out. I think they’ve always been there. I made a little ‘fairy’ out of grass and told my sister tales about her, and I told myself stories at night to help get to sleep. (What does this say about my stories if they put me to sleep?)

I wrote a very bad romance when I was in my teens, and read it to my long-suffering friends. They were very kind about it.

So I think I write to get these stories out of my head.

8. Why do you write fantasy?

When I was a student, I was doing teaching practice when a nine year old boy, with the wonderful name of Fred Spittal, asked me if I’d read Lord of the Rings. I hadn’t, and he recommended it, but said I should read The Hobbit first. I found both in the College Library and from there I was hooked. I read a lot of the fantasy that was around at the time and loved the way the authors built worlds out of their imagination. It’s still one of my favourite parts of writing fantasy.

9. From your About page, I know you love dogs. Do you have any pets at this time?

I don’t have any pets at this time, no. I didn’t think it was fair to have a dog while I was working as it would have to be left alone all day. Not good for a dog, which is a pack animal and needs company. After retirement we were going away a lot, so didn’t have any pets.

Growing up I had two dogs (not at the same time) a border collie, whom I called Laddie, and a corgi called Johnnie. I also had a budgerigar called Peter who was an amazing talker.

My stepfather was a farmer on the Cheshire/North Wales border and so there were plenty of animals around. There were the farm dogs, of course, and I had a cat called Frances who would sit on my shoulder. She was lovely.

Later, well after I’d married and had children, we had goldfish and three cats, although my husband doesn’t like cats!

10. If you could meet any three people, alive or dead, who would they be and why?

I would love to meet Leonardo da Vinci. Such a clever man–an artist, an engineer, a scientist, a medical researcher and more. We visited his chateau in Amboise, France and saw his inventions brought to life using only tools and materials from his day. Quite amazing.

You say three people. Someone I had (along with Leonardo) a picture of on the wall of my lab in school was Stephen Hawking. He was incredible. Not only did he have an amazing brain, but to do all he did with such a severe disability as Motor Neurone Disease, was incredible. His determination must have been second to none.

Finally, no, not a writer, but an artist. Any of the Impressionists, I think, but having visited his famous garden, I think I’d go with Monet.

11. Do you enjoy sport? Do you prefer to watch or take part?

Yes, I do enjoy sport. I used to play tennis, badminton and the occasional squash game, and when my daughter was at school and my son was small, I used to attend a session at the local sports centre aimed at mothers. They had a creche for the kids and we did some aerobics then volleyball, badminton or basketball.

Now, I don’t partake, but enjoy watching most sports (not golf though).

12. There is a photo of a lovely flower painting on your site. Do you still paint a lot? Who is your favourite artist?

I think I’ve answered the second part of your question alreaedy. I adore the Impressionists. I don’t think I really have a favourite amongst them, though.

As to the first part, I’ve not done so much recently. I have one partly finished, but it’s in oils and I don’t like to do it indoors as it creates a smell. I’m waiting for the warmer weather so I can finish it!

13. Do you do any voluntary work? If so, what?

I don’t do any voluntary work at the moment. I did work in the small park behind our house until recently. The park had become very overgrown, the council only cutting the grass. I contacted them and they looked it up. They told me it was supposed to be a ‘community project’. It seems the original volunteers had either died, moved away or grown too old, so several of us took it over. It looked nice for a few years, then the same thing happened. People moved away, and became too old. There was only myself and my husband doing it, and we’re getting older and finding it increasingly difficult, especially the heavier jobs. We do very little now, except for the occasional cutting back of overgrown brambles that are blocking the paths.

14. What do you think is the biggest problem facing the world today?

I think there are two. One is increasing selfishness and the other is stupidity.

From the person wanting to park their car as near as possible to their destination, regardless of inconvenience to others, to governments and large organisations who trample roughshod over anyone and everyone who gets in their way. Often stopping them getting what they want, up to and including taking over other people’s countries in order to get at the minerals etc that are there.

And threatening the whole future of humanity in not accepting scientifically proven things like Climate Change. And it’s not only governments who are becoming stupid, either. Individuals seem to have lost the ability to think for themselves.

Sigh…

Thank you so much for answering all my nosy questions, Vivienne. I’m sure my readers will enjoy discovering your books—those that don’t know them already, that is. Fantasy is very much the flavour of the day!

⭐️

For those interested, I am including links to Vivienne’s books below:

The Wolves of Vimar Series

The Wolf Pack

https://books2read.com/u/m0lxEy

The Never-Dying Man

https://books2read.com/u/3R6ozR

Wolf Moon

https://books2read.com/u/mvWjXe

Immortal’s Death

https://books2read.com/u/b6AYN0

Elemental Worlds

The Stones of Earth and Air

https://books2read.com/u/mYygKV

The Stones of Fire and Water

https://books2read.com/u/brwoVE

A Family Through the Ages

Vengeance of a Slave

book

https://books2read.com/u/3kLZxR

Jealousy of a Viking

book

https://books2read.com/u/bMYGKk

The Wolf Pack Prequels

Jovinda and Noli

The Making of a Mage

https://books2read.com/u/mddNNO

Dreams of an Elf Maid

https://books2read.com/u/4ElDZg

Horselords

https://books2read.com/u/31XQ0a

Poetry Books

Miscellaneous Thoughts.

https://books2read.com/u/38Pzpr