Going to the dentist is not my favourite outing, as one can imagine. Coming out of this morning’s visit, my mouth numb on one side, I nevertheless felt grateful to have been born in the twentieth century—in ealier ages, surely by now I would have had but a few teeth left, if any at all. The torture of toothaches and dentures must have been unbearable in those days.

In old portraits, people almost never smile. Smiling might have been considered uncouth and awkward, a serious face more dignified and also easier to get a likeness from, but another reason was that many people had bad or even missing teeth. Not very flattering, even if the subject was clad in velvet and lace.

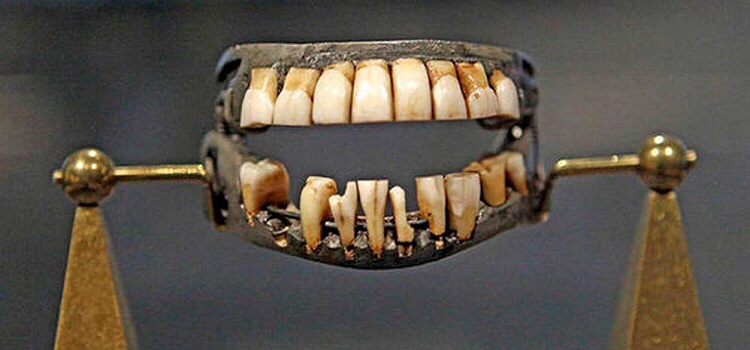

However, vanity (and practicality) made people look for solutions, starting in ancient times. The earliest known dentures—made by the Etruscans circa 700 BC, also found in Egypt and Mexico—consisted of human or animal teeth tied together with wires. Other ancient people use carved stones and shells to replace lost teeth.

In the 1700s materials improved with the introduction of walrus, elephant and hippopotamus ivory. But of course the best replacement was a real human tooth—acquired from people willing to sell them (these were difficult to find, because someone had to be desperately poor to give up his teeth) or, more easily, from corpses. Surgeons and professional grave robbers had access to these, but of course the most plentiful source was war. To get an idea of how many teeth were taken from battlefields, consider that they were sold by the barrel!

After the Battle of Waterloo there was a glut of teeth on the market. The French emperor, Napoleon, had lost 25,000 men, the Duke of Wellington’s mixed force had suffered 15,000 casualties and Blucher’s Prussians some 8,000. Viewed in the grey light of dawn the battlefield must have been a dreadful sight. But almost worse than the carnage must have been the arrival of an army of scavengers stripping dead soldiers (and some not so dead) of their valuables; coins, clothes, weapons and their teeth. Before long cartloads of teeth were heading for the Channel ports (I find this image hard to picture.)

There was already a well-established European export market for teeth, which had been started by one of George Washington’s dentists, John Greenwood, who in 1805 returned from Europe with a barrel load of human teeth from one of Napoleon’s earlier battles. George Washington suffered from tooth problems all his life, having lost his first tooth at 22; and he only had one of his own teeth left by the time he became president. He had several sets of dentures made, from various materials—but none, as popular belief has it, from wood (that is an urban legend). Some might even have been taken from slaves, another possible method for acquiring human teeth in those days.

The vast numbers of teeth flooding the London market became known as “Waterloo Teeth”. The belief that the teeth going into one’s dentures had once belonged to a brave young soldier had great commercial appeal.

However, there were already some alternatives to human teeth: The first porcelain teeth had been made in Paris by an Italian dentist in 1808. Despite that, and given that these alternatives had various flaws to start with, the demand for ‘Waterloo Teeth’ continued well into the second half of the 19th Century. At some point, due to the unbelievable slaughter of the American civil war, with over half a million deaths, the tooth trade was reversed, with millions of American teeth coming to Europe.

As for the dental health of the celebrities concerned, the Emperor Napoleon died in exile on St Helena in 1821 at the age of 52 still with all but four of his own teeth; and the Duke of Wellington lived until 1852, never having expressed a wish to acquire a set of Waterloo teeth for himself, despite having lost a few of his own.

Even as late as the 20th century, good dentistry was not available everywhere. Doris Lessing, whose parents moved to Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) when she was five, remembers seeing her mother secretly sobbing with pain: both her parents had all their teeth removed and replaced with dentures before going to Africa.

So hurrah for modern dentistry. And apologies for the gruesome tales and photos, but I found it interesting how difficult it has been to develop something we now take for granted. I’m sure the same goes for eyeglasses—Samuel Pepys suffered much from failing eyesight, and had to read holding tubes of paper or cardboard to his eyes. But that is another story.

Fascinating history, Marina! I can’t imagine the teeth of soldiers killed at Waterloo. I’m sure many would already have been in poor condition when the men died in battle.

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLike

I don’t think anyone likes going to the dentist, but modern dentistry makes it bearable.

My mother and her siblings had false teeth, as did my grandparents. I think few people got to old age with their own teeth in those days.

My generation was a little better. I have a number of crowns, but no false teeth (yet)! But my children and grandchildren have great teeth. All lovely and even thanks to the advances in orthodontics.

LikeLike

Fascinating, Marina! One of those quirky subjects that I have never thought about before. The image of people stripping dead (and, as you say, probably not so dead) soldiers of their teeth is a gruesome one. I don’t fancy the idea of someone else’s teeth, but then I am not looking at a life time of being toothless. I think it was common in my parent’s generation to whip out rows of teeth and have dentures, as it was thought to be better in the long run.

LikeLike

😬

LikeLike

At least the majority still had teeth, due to their relatively young age Marina. At seventy-five I have two and two thirds…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Have We Had Help? and commented:

Teeth. Not much to show for a life…

LikeLike

I too am grateful to have been born in this time of all sorts of technology and dentistry’s advancements. I hope your tooth is better today.

LikeLike

Thanks for that interesting read. It reminded me of the horrible scene in ‘Les Miserables’ where Fantine has her front teeth ripped out to make some money to feed her child.

Mind you, it’s so hard to find a national health dentist in the U.K . now that there are tales of people having to take out their own teeth with pliers or just suffer the pain as the cost of a private dentist are very high.

LikeLike

Gosh that’s a different take on war history. What an interesting read.

LikeLike

Very Interesting. I’d go for the carved stones.

LikeLike