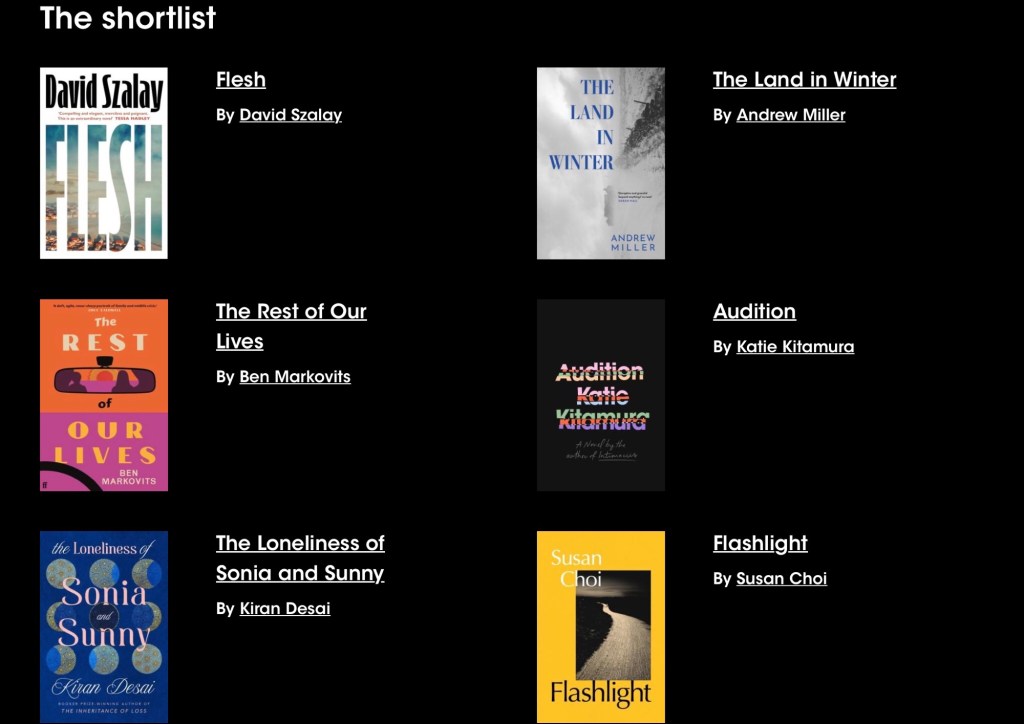

The Booker Prize season has come around again, and the shortlist has been published. Let me say at once that I have not read any of these books, but last year the list contained some pretty good stuff, so I am hopeful of a repeat, especially since Roddy Doyle is Chair of the 2025 judges and he knows a good story when he sees one.

I don’t suppose I will read them all, and I will look at some on the long list as well, but one I am looking forward to tackling is 700-page The Loneliness of Sonya and Sunny, by Kiran Desai (who has won it before in 2006 with The Inheritance of Loss.) It reminds me of another doorstop, A suitable Boy by Vikram Seth, which I devoured at the time. Many years in the making, it is an epic tale of love and life.

Flesh, by David Slazay, is (I quote the Booker Prize site): “A propulsive, hypnotic novel about a man who is unravelled by a series of events beyond his grasp.”

The Land in Winter, by Andrew Miller, is about two couples, a doctor, a farmer and their respective wives, whose lives are upended in the middle of a harsh winter landscape.

The Rest of Our Lives, by Ben Markovits, is about a middle aged academic who goes on a road trip after his wife has an affair, trying to escape his problems.

The last three all seem to be about lives unravelling. Hmm…it depends how each writer deals with the subject.

Audition, by Katie Kitamura, is about the relationship between two very different people: an attractive actress and a man young enough to be her son. Intriguing.

Flashlight, by Susan Choi, is a saga about a father’s mysterious disappearance and the reverberations of this event on his family.

All six authors are deep into their literary careers, with a number of books to their name and, besides previous winner Kiran Desai, Andrew Miller and David Szalay have been shortlisted before.

If (or when) any of you read any of these books, I will be glad of an opinion. In any case, a pile of new books is always enticing, even if at the moment it is not on my shelf but only on my screen.