On Throwback Thursday I thought I’d post something I started writing some time ago after a trip to Morocco, but for some reason I never finished. It was a beautiful place, and the photos brought back nice memories.

Not far from the Marrakech medina and overlooked by the majestic, snow-capped Atlas Mountains, there is a magical garden combining art with a profusion of beautifully planted trees, bushes and flowers of all kinds.

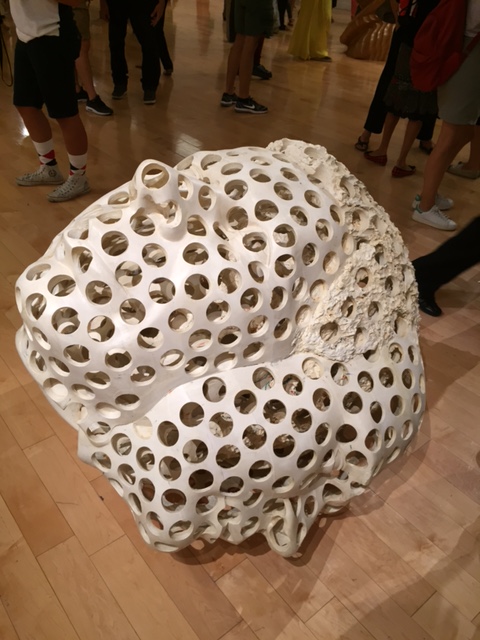

The garden is laid out with paths meandering through the vegetation and interspersed with astonishing sculptures by various artists, some very well known.

Here’s one by Keith Haring below:

The place has the most unusual vibe: it is at once peaceful, joyful and alive.

The garden is the creation of acclaimed Austrian artist Franz André Heller. Here’s a short bio from the Anima site:

André Heller was born in Vienna in 1947. He’s among the world’s most influential and successful multi-media artists.

His achievements encompass garden artwork, chambers of wonder, prose publications and processions including a revival of circus and vaudeville, selling millions of records as a chansonnier of his own songs, amazing flying and swimming sculptures, the avant-garde amusement park Luna Luna, films, fire spectacles, and labyrinths as well as stage plays and shows that have entertained audiences from Broadway to the Vienna Burgtheater, from India to China, and from South America to Africa.

André Heller lives in Vienna, Marrakesh, and on the road.

There is a lovely café in the garden, named after writer Paul Bowles,and plenty of hidden benches where people sat reading or just soaking in the atmosphere. There are even a couple of colourful striped hammocks where you can lie in the dappled shade.

A very well-dressed gentleman, above.

My absolute favourite was an alley lined with stone columns, each with a carved animal upon it.

Each more charming than the next.

My one caveat is that there are no identifying labels anywhere, so there is no way of knowing who the artist is, unless they are universally recognisable, like Picasso or Rodin.

So if anyone recognises the artist who made these delightful animals, please let me know.

This visit was one of the highlights of a short break in Morocco, and is most highly recommended, should you be somewhere in the vicinity.