When I bestride him, I soar, I am a hawk: he trots the air; the earth sings when he touches it; the basest horn of his hoof is more musical than the pipe of Hermes. ~William Shakespeare, Henry V

Man and horse have been linked since time immemorial. Horses appear in cave paintings, such as this one from Lascaux, in France.

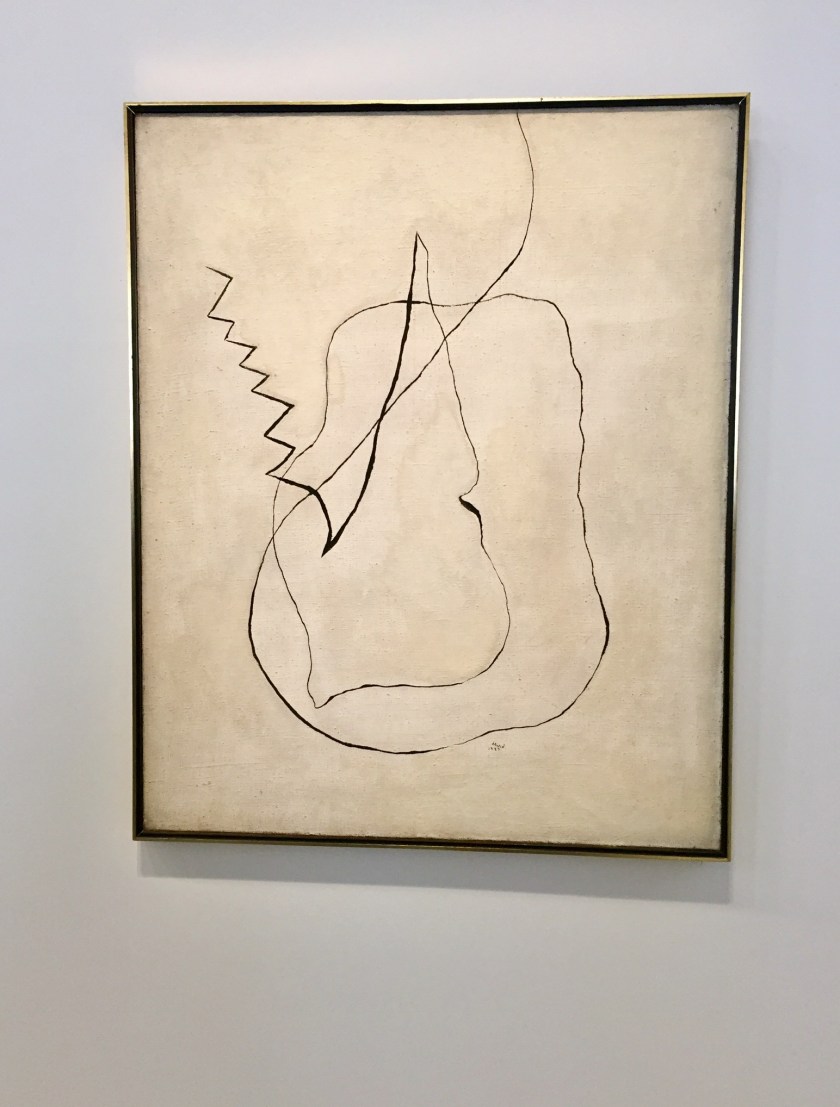

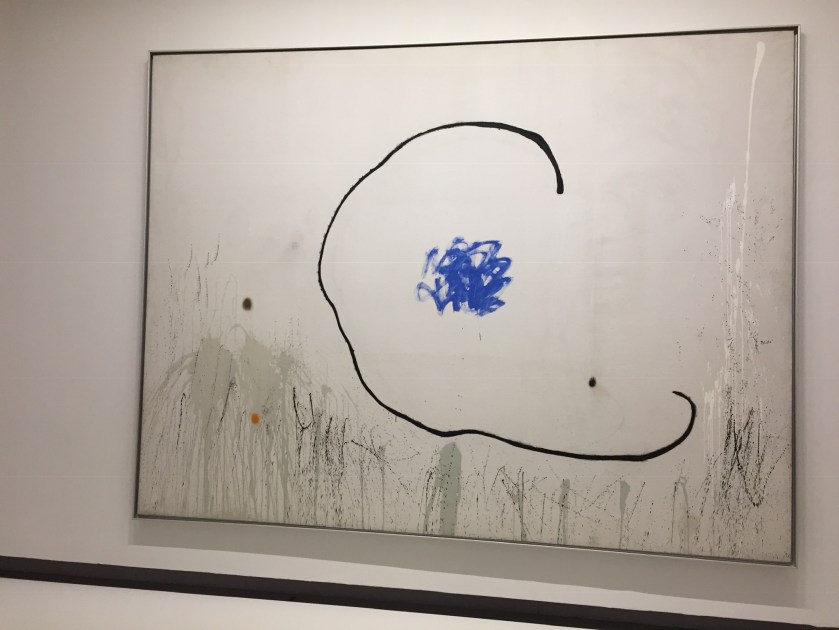

We find them on Ancient Greek pottery,

and in the wonderful Parthenon marbles.

The horse has been depicted by a multitude of great artists, and lauded in poetry and prose:

How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix

I sprang to the stirrup, and Joris, and he;

I gallop’d, Dirck gallop’d, we gallop’d all three;

‘Good speed!’ cried the watch, as the gate-bolts undrew;

‘Speed!’ echoed the wall to us galloping through;

Behind shut the postern, the lights sank to rest,

And into the midnight we gallop’d abreast.

Robert Browning

Let us nudge the steam radiator with our wool slippers and write poems of Launcelot, the hero, and Roland, the hero, and all the olden golden men who rode horses in the rain.

Horses and Men in Rain by Carl Sandburg

The Mourners

When all the light and life are sped

Of flowing tails and manes,

And flashing stars, and forelocks spread,

And foam-flecks on the reins;

I like to think from every land

And far beyond the wave

A crowd of ghosts will come and stand

In grief around that grave –

Will H. Ogilvie

There is nothing so good for the inside of a man as the outside of a horse. ~John Lubbock, “Recreation,” The Use of Life, 1894

Horse sense is the thing a horse has which keeps it from betting on people. ~W.C. Fields

The wind of heaven is that which blows between a horse’s ears. ~Arabian Proverb

Horses have been part and parcel of our civilization.

Where in this wide world can man find nobility without pride,

Friendship without envy,

Or beauty without vanity?

Here, where grace is served with muscle

And strength by gentleness confined

He serves without servility; he has fought without enmity.

There is nothing so powerful, nothing less violent.

There is nothing so quick, nothing more patient.

~Ronald Duncan, “The Horse,” 1954

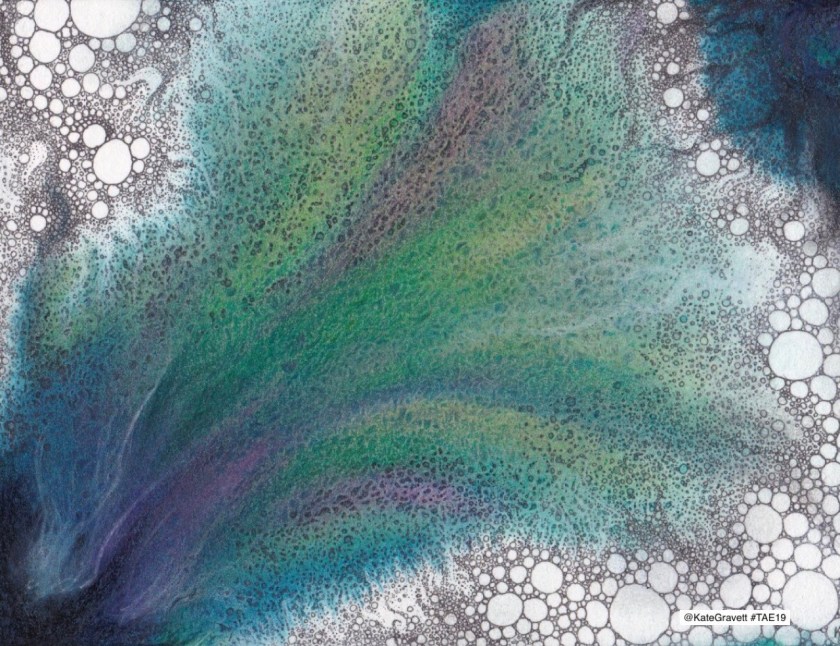

This short miscellany which does not pretend to cover even a tiny part of the subject, has been an inspiration for a series of mixed media paintings of horses that I’ve been making.

Photos: Google

All photos from Google

All photos from Google